On October 2, 1959, John Howard Griffin made his first diary entry, the first of many that would then go on to form the content of his book Black Like Me. These recounted Griffin’s experience as a white American novelist, going undercover in the Deep South to “authentically” report what it was like to “experience discrimination based on skin color, something over which one has no control”. After having taken oral medication for skin pigmentation, and subjecting himself to ultraviolet rays, cutting his hair so that he would look “slick” for the women, and shaving the fair hairs from his hands, he set off, alone, down South.

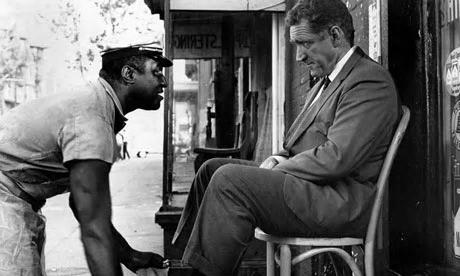

Black Like Me is composed of a series of journalistic entries, during which the reader is positioned within an intimate ethos frame with the writer. The book as a whole is never static, it moves as Griffin moves, whether he is on a bus, hitchhiking, walking down alleyways in search for a bathroom that coloured people were permitted to use, or even carrying out the simple action of shoe shining. He is forever in motion throughout the narrative. A narrative that emphasizes the bigotry of the white man, and the kind and welcoming nature of the black man.

As readers, however, where does our empathy actually lie? Griffin was a white man “imprisoned in the flesh of an utter stranger, an unsympathetic one with whom [he] felt no kinship”. Indeed, on November 7, he looked at himself in the mirror for the first time after his transformation. He felt loneliness, and distress. He then began his journey disguised as a black man, wondering the streets in search for new experiences.

Personal narratives of black individuals often evoke a sympathetic reaction in a white audience. However, with Griffin constantly emphasizing the existence, and consequently the difference, of the “two men” in his body, does the reader still feel this way?

Does his transformation imply a wider gap between the white and the black individual, or a smaller one? We have a white author, deceiving the Southern world to “get a story”, manipulating individuals and treating them as if they were animals on which it was perfectly normal to experiment. On the other hand, we have a dedicated journalist who goes to great lengths in order to provide the white reader with something as truthful as possible, in the hope of raising awareness of the damaging effects of segregation.

A white man posing as a black man does not, and can not, understand the extent to which segregation has damaged humanity; he does not understand the anger and pain that come with hundreds of years of slavery and inhumane treatment. Discrimination has far deeper roots than anything that could possibly be imagined, nor rectified by a book like this. I applaud his efforts, as I believe they are benign and good-hearted, but I feel that the book is patronising as a whole, and does not even begin to cover what, or how, the black individual felt, and in part still feels today.